The student protests that engulfed campus from March 2015 onward centred around the sculpture of Cecil John Rhodes, but expanded to include other artworks. Colonial-era portraits from Smuts and Fuller Hall, both upper campus residences, were added to a bonfire in the adjoining parking lot and set alight. Perhaps these artworks could be regarded as expected casualties in an escalating fracas that targeted the pervasive culture of ‘whiteness’ and Euro-centric cultural hegemony on campus. The portraits predominantly depicted former white male academics and could be viewed as reinforcing the perception of UCT as fostering a culture of exclusion. But the destruction of artworks by African artists and apartheid-era activists such as Richard Baholo and Molly Blackburn, which were also added to the bonfire, seemed to contradict the movement’s basic tenet and has generated much conjecture.

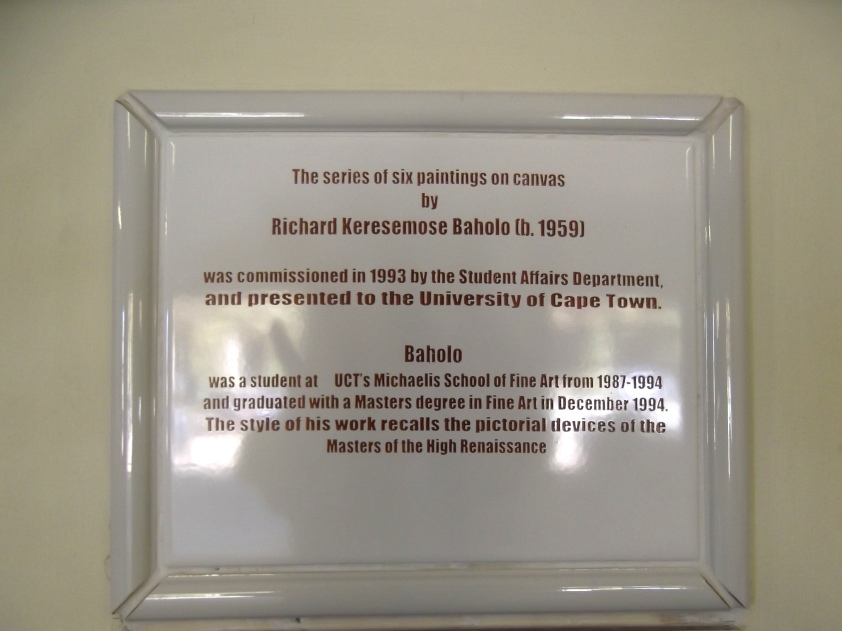

In order to attempt to make sense of why this happened, it is necessary to take a closer look at the exhibition space from which Richard Baholo’s paintings were seized. Consider the way in which following inscription that is found on a plaque in the Otto Beit building has been culturally encoded:

“Baholo was a student at UCT’s Michaelis School of Fine Art from 1987 – 1994 and graduated with a Masters degree in Fine Art in December 1994. The style of his work recalls the pictorial devices of the Masters of the High Renaissance”.

This plaque serves as the framing narrative for the entire collection of paintings that was exhibited in the space, and as such it would have coloured a viewer’s appreciation of all of the artworks in the room. Its inclusion here effectively deprived the viewer of an independent perspective, since it pre-defined how the artworks were to be approached, both historically and analytically. It also offered a characterisation of the artist which emphasised his conformity to accepted European standards of artistic practice and representation while admitting no particularly original influences – whether African or otherwise. It essentially praised the artist for faithfully imitating other acknowledged master artists. While the intention may not have been to reduce the artist’s achievement to mere imitation, it has effectively deployed a familiar trope of colonial representation, namely, that of the ‘good black’ who follows the rules and does as he is supposed to do.

In decoding the cultural narrative provided on the plaques, any black African student would be right to feel a deep sense of unease at the way in which the artworks, and the artist, have been portrayed. If the narrative is accepted, then Baholo is to be regarded as no more than a skilled imitator and one who is possibly complicit in the hegemony which denies black Africans their cultural identity. If the narrative is rejected, then the university is evidently implicated in the denigration of African art and culture.

While it cannot be said conclusively if this interpretation of the art collection’s framing narrative formed part of the reason for the burning of Baholo’s paintings, it does provide compelling evidence of how such artworks may have been perceived as problematic.

What is most surprising of all is that, while the artworks have been removed from the walls, the plaques and their highly questionable framing narrative remain on display.

Navigate through this project using the site index.